Four months ago, we had the pleasure of giving you the first part of William York’s essay on Mr Bungle. He detailed out the genesis of the first band and their first few years. Now we got the second part for you in which he talks about the later period of the band that turned musicians into all-stars and their vocalist into the superstar that he was before Faith No More and that he still is to this today. We are happy to give you this second part and are sure, you will like it!

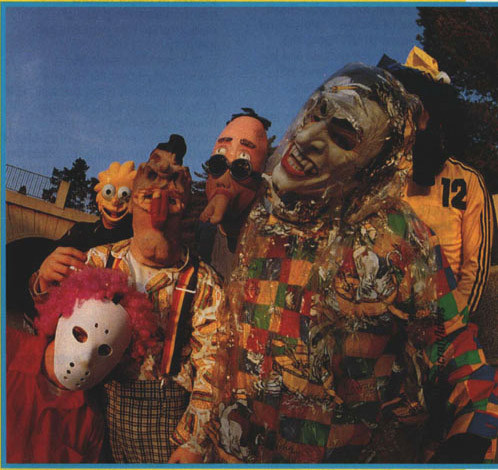

Interviewer You guys started out as this Death Metal band, so how did you evolve into this carnival-type terror?

Trevor Well, Death Metal was always kind of a carnival thing to us because up in Humboldt County when you ride the Zipper, they play Slayer.

Theo Cuz “carne” means meat. And meat is death.

Trevor And death is death metal….

(Waffle Issue #2 , 1992

)

A few months ago, when I was still wrestling with Part 1 but also trying to figure out my angle for the eventual Part 2, I made a fortuitous pickup at the local used bookstore: a slightly worn but reasonably priced copy of Soren Kierkegaard’s The Point of View for My Work as an Author.

The book – written toward the end of his life but withheld from publication until after his death – was intended as an overview of the philosopher’s voluminous and at times perplexing writings, which I’ve recently been delving into for reasons otherwise unrelated to this article.

On the very first page, Kierkegaard announces, “The contents of this little book affirm that I am and was a religious author” - as opposed to, say, a mere philosopher (or “aesthetic author,” as he puts it).

I read this and thought, “A-ha. There’s my angle for the second Mr. Bungle piece.” That is, I could make the case that just as Kierkegaard was always a religious author – even when he wasn’t writing about religion – Mr. Bungle were always a metal band – even when they weren’t playing metal. What better way to follow up my defense of the Raging Wrath of the Easter Bunny lineup in Part 1 than to double down on it: “Not only is the Raging Wrath material legitimate, it’s the very essence of the band!”

In this light, The Raging Wrath of the Easter Bunny Demo — together with the various interviews done in conjunction with it – could be seen as a kind of musical analog to Kierkegaard’s posthumous volume: “The Point of View for Our Work as a Band.” After all, as guitarist Trey Spruance himself put it in a 2020 interview with Revolver Magazine</a>: “Everything we ever did was metal in a way.” My task would simply be to spell it out – to clarify the sense in which, say, “Pink Cigarette” or “The Bends” were actually the work of a Metal band, all appearances to the contrary.

Alas, I couldn’t quite pull it off. Maybe I lack the requisite boldness, or maybe I’m just allergic to sweeping generalizations. Certainly, there is much that could be said about the subtler ways in which Mr. Bungle’s metal background influenced their outwardly non-metal material (a topic I return to below). But to focus exclusively on that angle would be to obscure the equally important sense in which they were not a metal band, or at least not a typical metal band – even when they recorded the original Raging Wrath of the Easter Bunny cassette back in 1986, and even when they were headlining the Milwaukee Metal Fest earlier this year.

But how can these two things be true at once?

To make sense of this all, it might help to go back to the place where it all started: Eureka, California, circa 1985. “It would have been a fairly weird place to grow up,” observed drummer Danny Heifetz when I interviewed him in 2016. “It’s a fairly redneck kind of place. It’s a lumber town.”

A few hundred miles down the coast, the Bay Area Thrash scene was in full swing. Metallica and Exodus had already released landmark albums, and other, more extreme mutations were already bubbling up to the surface.

Chief among those was Possessed, an East Bay outfit who are widely credited with coining the name of a new genre: Death Metal. This was the title of their 1984 demo tape as well as the last song on their debut album, Seven Churches, released in November 1985 (the same month, incidentally, as We Care a Lot, the debut album by a little-known San Francisco outfit known as Faith No More). The Raging Wrath of the Easter Bunny, in turn, was recorded in the early months of 1986 and released later that year. So, if Mr. Bungle weren’t quite at ground zero for the initial Thrash/Death Metal explosion, they were at least downwind of it – both geographically and chronologically. In other words, they were close enough to feel a connection to it, but also isolated enough that they had to figure out the details for themselves.

“I was a fuckin’ greasy teenager who loved Venom and Possessed, and that’s sort of what I was trying to do – sound like them,” explained an uncharacteristically forthright Mike Patton in a 2020 interview with Loudwire: “In your mind, that’s what you think, but when you listen back you’re like, ‘Wait, this is a little bit weird.’ ”

Spruance made a similar point in a 2017 interview with Luis Misiara: “You were imagining, ‘Wow, when these bigger bands like Slayer play, it must be like this,’ and it definitely isn’t.” (Medium interview, 2017)

Yet as earnest as they may have been about emulating their metal heroes, no one could accuse the teenage Mr. Bungle of being overly reverent toward the genre. Their performance at the Eureka High School talent show in 1985 featured (among other things) a sarcastic version of Mötley Crüe’s “Shout at the Devil,” with intentionally limp vocals by Patton. The band name was another clue: they weren’t Death, or Death Angel, or Morbid Angel; they were … Mr. Bungle.

“We were a metal band,” clarified bassist Trevor Dunn in an episode of the In Defense of Ska podcast, “but we also liked the idea of making fun of metal, like not taking it too seriously.”

And therein lies the conundrum. Metal is serious business, and attempts to leaven it with humor are typically fraught with peril. Here I’m reminded of a line from an article about Earache Records that served as one of my introductions to the genre when I first read it some 25 years ago: “One thing to remember about Metal of all types: If it is supposed to be funny, 9 times out of 10 it is definitely neither worth listening to or humorous.” (Earache Records: A Grindcore Post-Mortem) The flip side is that the funniest things in metal tend to be unintentional, or at least that’s how they come across. Both of these points apply when it comes to the original Raging Wrath demo. The two more lighthearted tracks - “Evil Satan” and “Hypocrites” - are also the weakest ones. Meanwhile, the funniest moments come via Spruance’s exploding “video game” guitar solos – which, incidentally, are metal through-and-through.

Tellingly, “Evil Satan” was the only song from the original demo to be omitted from 2020’s Raging Wrath redux. Yet it was also the only song to reappear on any of the later demos, as a re-recorded version of the song appears on 1987’s Bowel of Chiley, At the time, this drastic shift in musical direction – away from metal and toward the hyphenated Circus-Funk-Ska hybrid that would prevail on the next couple of demos – was not unanimously well received. According to Small Victories author Adrian Harte, Faith No More guitarist Jim Martin told Patton (not yet a member of FNM at this point), “The Raging Wrath of the Easter Bunny is the way to go, Bowel of Chiley is no go.”

The Raging Wrath remake suggests that Patton and company agree with this sentiment, at least in hindsight. At the time, though, it was their interest in other kinds of (decidedly non-metal) music that won out, from Ska bands like the Specials and Madness to fellow Californians Fishbone and Camper Van Beethoven. Video game music was another influence, along with (yes) Rap and Funk. “At the same time,” adds Spruance, “we were studying our asses off – Trevor and I – studying Messiaen and Stravinsky and all this atonal theory stuff.” In short, it was a time of trial and error for the band.

By the time of their debut album, the metal elements had reasserted themselves somewhat. The album versions of demo-era songs such as “Carousel” and “Love Is a Fist” are heavier, in a metal sense, than the demo versions, and newer songs such as “Travolta” and “My Ass on Fire” also contributed to upping the metal quotient.

Even so, the group’s early days as a Thrash/Death metal outfit were seemingly a distant memory by this point, having been overshadowed by Patton’s more recent star turn in FNM. When the topic did come up in interviews, it was almost like the band members were daring others to believe them. “Trevor and I wore more spikes and stuff,” Patton told Kim Edwards in a 1991 interview. “We still are a Death Metal band. That’s very important to know. No one ever notes it.”

Yet it’s not as if one could simply take Patton (or any of the band members) at face value in those days. “I mean, we didn’t think of ourselves as a metal band by the time our first record came out,” Spruance admitted to me in 2005. “Not even close.”

Part of that shift had to do with the more recent additions to the lineup: drummer Heifetz and saxophonist/keyboardist Clinton “Bär” McKinnon. “I definitely don’t think of Bär as a metal head,” Heifetz told me. “I was a metalhead, but in a totally different era. Even though I’m only four or five years older, I was like a generation away. I really couldn’t have cared less about Metallica. Didn’t like Slayer. When I was 14, 15, I was listening to Judas Priest, Black Sabbath, and…not even really metal, just heavy rock. Richie Blackmore’s Rainbow. Early Scorpions. That was my metal. That’s just like a totally different world.”

At the same time, there’s a reason why the two of them were brought onboard in the first place—namely, the group’s continued interest in other kinds of music besides just metal. This dovetails with the various members’ activities after they relocated to San Francisco in 1991. Patton was the one getting all of the media attention, but the others kept equally busy by lending their talents to a variety of projects: Punk pranksters the Pop-O-Pies (Spruance and Heifetz) and Plainfield (ditto); country-rockers Dieselhed (Heifetz); and Amarillo Records misfits Faxed Head (Spruance, anonymously). Meanwhile, Dunn was honing his upright bass skills, playing alongside pianist Graham Connah and a variety of others from the Bay Area jazz/improv scene. There were also collaborations with John Zorn and others from the Downtown New York scene, not to mention exposure to all sorts of obscure music ranging from German film soundtracks to Bollywood and beyond.

Apart from Faxed Head, none of this had anything to do with metal. Yet as 1995’s Disco Volante attests, the metal influences were still there. Indeed, this was the first time since The Raging Wrath that one could speak of death metal as an actual ingredient in the band’s music. You can hear it most prominently on “Carry Stress in the Jaw” and “Merry Go Bye Bye,” but it’s also audible in parts of “Ma Meeshka Mow Skwoz,” “Platypus,” and “Phlegmatics” (and, more abstractly, on “Desert Search for Techno Allah” and “Violenza Domestica”). Even the guitar-less, organ-heavy “Chemical Marriage” contains some heavy bass/percussion hits that feel like Death Metal power chords. Percentage-wise, these “Death Metal bursts” make up a small part of the album, but they nonetheless act as a kind of glue that holds the other disparate elements together.

That said, Disco Volante wasn’t necessarily perceived as a metal album when it came out. Generally speaking, critics didn’t know what to call it. “To classify the music performed by Mr. Bungle is an exercise in futility,” wrote one reviewer. Others compared it to Frank Zappa and the Residents or dismissed it as a self-indulgent side project by “Mike Patton’s other band.” Certainly, the Patton/Faith No More connection was responsible for a large portion of the band’s audience, though with Disco Volante, that audience also grew to include part of the John Zorn/Naked City crowd, who could hear in Mr. Bungle some of the same hyperactive, cut-and-paste creativity that characterized Japanese outfits such as Boredoms, Ruins, and Ground Zero.

Over time, though, the record has come to be viewed as a touchstone of so-called avant-garde metal (even if it is more than just that). This point hit home last summer when I interviewed Camille Giraudeau, a multi-instrumentalist whose bands include Dreams of the Drowned and Stagnant Waters – neither of which strike me as particularly “Bungle-ish.” “My first real introduction into avant-garde metal per se was Disco Volante by Mr. Bungle in 2000,” he told me. “And then from there, Focus by Cynic. And then through Ulver, I found Virus, because Carheart was released by Jester Records. And then there was like an obsession which arose, and it was kind of a reprogramming of my ears. And so through Virus came Ved Buens Ende, Fleurety, Dødheimsgard….”

Those last two bands, along with fellow Norwegians Arcturus and Solefald (and non-Norwegians such as Japan’s Sigh), would end up making albums during the late 1990s/early 2000s that echoed various aspects of Disco Volante - particularly the multi-color arrangements and non-linear song structures. Whether or not DV was a direct influence, it was at least a precursor to albums like Arcturus’s La Masquerade Infernale (1997) and Dødheimsgard’s 666 International (1999). Like Disco Volante, these were cinematic, studio-intensive albums that were nonetheless rooted in metal.

Of course, by that point, Mr. Bungle were onto something different yet again. With California, they took the term “studio-intensive” to a whole new level while also dialing back the metal significantly.

Perhaps not surprisingly, it was with California that my initial (failed) attempt at writing this article ran aground. “If everything they ever did was metal in a way,” I asked myself, “then in what way was California metal?” And after much reflection, I can think of a couple of ways, beyond the brief bursts of metal guitar that punctuate a few of the songs.

One is the lyrics, particularly the ones penned by Dunn (“Retrovertigo”, “The Holy Filament”) and Spruance (“None of Them Knew They Were Robots”, “Golem II: The Bionic Vapour Boy”). Mind you, California was billed (however ironically) as the band’s “pop album,” but these lyrics – with their philosophical themes and polysyllabic vocabulary—are too convoluted for pop music. And while they don’t traffic in typical metal themes, they are much closer in style to the kind of thing you’re likely to hear on a death metal record than in a Top-40 song.

The other is the actual construction of the music. On the one hand, the album openly refers back to bygone varieties of popular music, from the Beach Boys and Burt Bacharach to 50’s Doo Wop and Exotica. On the other hand, the recordings were assembled with the kind of precision and attention to detail that is a hallmark of metal musicianship. With the exception of “Ars Moriendi”, the music itself wasn’t particularly technical, but the recording process certainly was—to the point that pieces of studio equipment were literally sagging under the weight of all the audio cables by the end of the sessions (2019 Interview with Trey Spruance, to be found on FaithNoMorefollowers.com). “Mr. Bungle’s a technical challenge,” Trey told me in 2002. “It’s not a place to explore your fuckin’ soul or anything like that.”

But as for the music itself? It isn’t metal, nor is it trying to be.

If California had truly been the end of the line for Mr. Bungle, it would have been easy enough to conclude, “Oh well, they had their metal phase, but they matured and grew out of it.” This was the impression Patton gave in a 2002 interview with the East Bay Express. “The first record we did was kind of cornball, goofy, tongue-in-cheek, inside-joke crap,” he said, referring to the Raging Wrath cassette. “And that’s exactly what it is: Crap.” (2002 Interview with Mike Patton with East Bay Express) Seen in this light, the group’s recent reincarnation as a metal quintet would appear to be a form of regression, of de-evolution.

But it isn’t quite so simple. Even during the California tour, they were known to dust off Raging Wrath standout “Raping Your Mind”, and even if Patton’s vocals on it came across as self-mocking, it was clear that they hadn’t totally disowned this part of their past. Meanwhile, the band members’ other projects — including Fantômas, Secret Chiefs 3, and even Dunn’s Trio-Convulsant - revealed that metal was still very a much a part of their musical DNA.

And here, oddly enough, is one place where I can draw a parallel with Kierkegaard. In The Point of View…, he describes his strategy of alternating between what his philosophical (or “aesthetic”) works and his religious (or “edifying”) ones. He did so, he says, in order to avoid giving the impression that religion is something to put off for later in life, or even that aesthetic concerns cease to be relevant at some point (e.g., after one has “grown up”).

In their own way, Mr. Bungle’s return to their metal roots tells us something similar about their relationship to that music (and, by extension, to Eureka). Yes, they’ve grown and evolved over the years, but that doesn’t mean they can’t still get up there and play “Anarchy up Your Anus” like they mean it.

There were moments during the Raging Wrath shows when you couldn’t help but wonder, “What if they had stuck with this style all along?” They could have become Gods of Metal in their own right. Yet as soon as those thoughts would start to percolate, they would veer into a cover of Seals & Crofts’ “Summer Breeze” or 10cc’s “I’m Not in Love” and take the air out of the balloon — just like they would have done back in Eureka in 1985.

For Spruance, the recent Raging Wrath tours acted as a sort of recapitulation of the band’s early years. “It seems like we started with this very limited language,” he told the Australian website Maniacs Online in an interview earlier this year, “and now it’s blossoming out from that, almost like the beginning of the band, when started from this Death Metal shit to begin with and then started exploring other genres. It’s sort of repeating that process.”

About the author:

Will York is the author of Who Cares Anyway: Post-Punk San Francisco & the End of the Analog Age (Headpress) and the host of the Who Cares Anyway Podcast as well as a new podcast, Fatal Strategies, debuting this fall.

Related interviews:

Veil of Sound interviewing Bär McKinnon

Veil of Sound interviewing Michael Crain on Dead Cross

Veil of Sound interviewing C*NTS, also on Ipecac