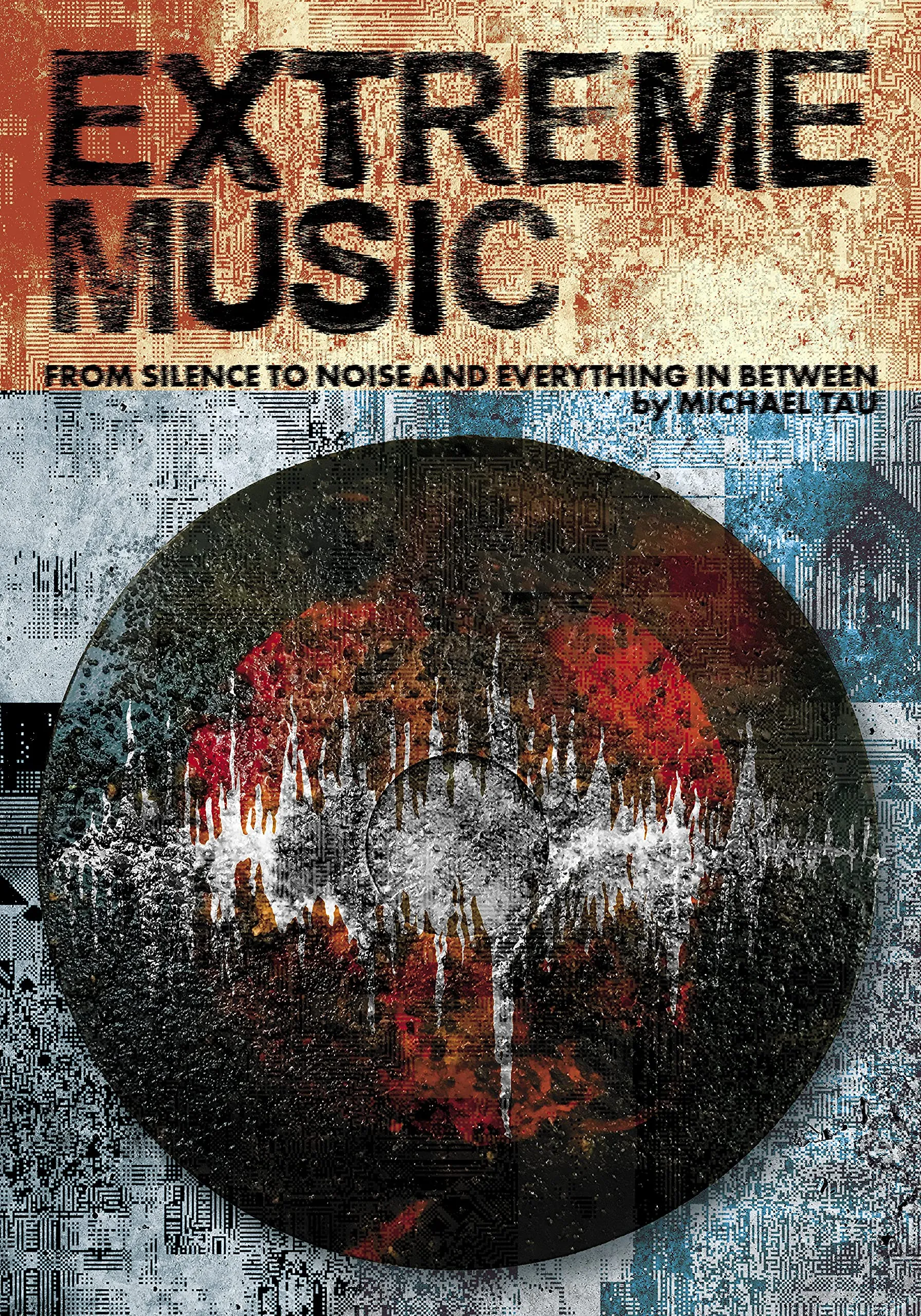

Again, something out of the ordinary for VoS will be this Special. Feral House, one of the most interesting publishing houses and VoS will work together on the release of the brand new book by established music nerd and journalist Michael Tau, who has been working on a magnificent compendium of anything related to extreme music in his new book Extreme Music: Silence to Noise and Everything in Between. Today we give you a first-hand look into the book via a good, lengthy excerpt plus an intriguing chance at the bottom of the page!

Michael Tau has long been trying to publish this affair du coeur, a matter of the heart, as he has been longing to show the development of modern avantgarde music, noisey and ambient, rowdy and soothing for decades. His new book does just that, it shows up the lines along which that kind of music has grown over the last decades. After having enjoyed a read through an early copy I can re-assure you that he has achieved something important because his work clearly clarifies the big lines via an in-depth-analysis of the smaller examples.

The following is an excerpt from “Chapter 1.1.2 - Noise Music”

For me, the aesthetic of loudness reaches its epitome in noise music, one of the rare music genres that truly lives up to its name. Imagine an entire scene of producers composing lengthy passages of abrasive white noise, usually by turning the dials on their equipment up so far that all that remains is feedback.

Paris-based producer Romain Perrot, a leading figure in noise music, captures the noise aesthetic in an interview with Quietus:

“I’d encourage anyone who is interested in finding out more about noise who hasn’t listened to it before just to take a radio, tune it to between two stations, and turn up the volume. If you can see the appeal, then perhaps it is time to investigate harsh noise in a little more detail.”

In fact, in 2014, a minor uproar surfaced in Cleveland after a DJ at Case Western University’s campus radio station, WRUW, was told by his station manager to stop playing Perrot’s music for fear that listeners were confusing it with radio static and tuning out.

Noise as a concept is nothing new, and it has been a feature of experimental music dating back to the early twentieth century, from the recordings of Futurist artist Luigi Russolo through to the work of John Cage and the musique concrète composers. But many consider Lou Reed’s 1975 double album Metal Machine Music, to be a seminal event in noise. Like much noise music to come, even that first album was shrouded in controversy. It’s been rumored that Reed recorded it as a cynical gesture to fulfill his label’s contractual obligations, or that it was a joke directed at his fans. In the liner notes, he claims that he didn’t even listen to the whole thing before its release. A groundbreaking alternative music reference book, the Trouser Press Record Guide, had a lukewarm take on the record: “If he was simply looking to goad people and puncture perceptions, Metal Machine Music was a rousing success.” Elsewhere, Rolling Stone magazine described it as “the tubular groaning of a galactic refrigerator.” Despite mainstream revulsion, MMM’s sound was an influential one. Today, it is seen as a key progenitor to a noise scene that developed in the late seventies and early eighties. Around then, a subculture of Japanese musicians started putting out cassettes filled with harsh noise, primarily using electric guitar reduced to feedback by effects units.

Several big names emerged from this Japanoise scene, many with exotic names that hinted at noise’s cold industrial overtones (MSBR, short for Molten Salt Breeder Reactor) and curious relationship to the vulgarity of the human body (The Gerogerigegege, a Japanese onomatopoeia for vomiting and expelling diarrhea at the same time). Their noise often reveled in debasement and excess. The Gerogerigegege, a duo particularly fond of extremes, had a member named Gero 30, whose sole responsibility was to masturbate on stage, most famously by using a vacuum cleaner. Reportedly, both members of The Gerogerigegege would sometimes play with, and even eat, feces onstage.

But no noise act was as big as Merzbow, the pseudonym of Masami Akita, whose career has spanned five decades since his 1980 debut tape, Fuckexercize. An oft-cited noise music quotation is attributed to him: “If by noise, you mean uncomfortable sound, then pop music is noise to me.”

Merzbow’s discography is unquantifiable, given the many lost releases along the way, but the website Discogs lists 374 official standalone releases, not including compilation appearances. The pièce de résistance is 2000’s Merzbox boxed set, an elaborately designed stalwart on the Extreme label that entails fifty CDs of harsh noise. One thousand copies of this impenetrable bombshell were produced, selling at $450 USD apiece. A couple decades later, Extreme Records’ Roger Richards estimates that fewer than 120 copies remain unsold.

Many people argue that noise is a rejection of everything that makes music appealing as a commodity. And yet the massive noise pantheon, with its enormity of ultra-limited edition releases, has produced a gigantic collectors’ market. Obscure Japanoise tapes and records routinely sell for hundreds of dollars, and opportunistic record dealers have been known to monitor the release dates for recordings on labels like Hospital Productions and then buy up copies to immediately sell at multiples of their original price.

I asked Richards whether he thought the Merzbox, a slick item in a fancy case with various collectible odds and ends, was incompatible with noise as an anti-consumerist enterprise. He doesn’t doubt that it’s been fetishized by some, but he thinks that’s a price worth paying. “I’m sure that some people do buy the Merzbox as a collector’s item and never listen to the music. No doubt! The soft rubber Merzcase is a playful hint to this. But I also know that some have ventured into the many dimensions of noise music through the Merzbox — be it listening to other noise musicians or creating noise music themselves.”

He points out that, like noise, many genres started out with an anti-consumerist message. “Punk, rock, and industrial to name a few.” And while noise “has stood the test of anticonsumerism for many years for some would say obvious reasons,” there have begun to be “fragments of noise entering pop music which is certainly a commodified music form.”

But noise is also interesting because it’s been written about quite prolifically from the standpoint of theory. Several papers and books have been published on the subject, most notably Japanoise: Music at the Edge of Circulation by David Novak and Noise/Music by Paul Hegarty. Reading Hegarty’s musings on noise can be intense, as he parses concept after concept, becoming exponentially more abstract. I admire his love for the obscure details of the Japanese noise scene, although I somewhat resent his writing style, which amounts to reading sentence after sentence of this:

“This double failure—not being noise, not being music—is the only fleeting success noise can have. This is not negative, except at the level of noise being a negativity—i.e., noise does not positively inhere in a specific piece or style of music, it occurs in a relation.”

You might be wondering what there is about static noise that warrants this sort of dense theorizing. Consider that noise, whose etymological origins stem from the Greek word nausea, refers to something broader than the phenomenon of geeks in non-prescription glasses rubbing contact mics through their pubic hair. Noise refers to stimuli that are gut-churning or aversive. Many define noise by what it is not — whereas music is “organized sound,” noise is everything else. But what does that mean for those who prefer to listen to noise instead of “organized sound,” or those who organize harsh noise into sound sculptures?

Hegarty summarizes several different theories of noise in his essay “Noise Music.” One theory sees noise as a triumph of the physical over the rational, a cathartic experience that can bring people together—the rave scene in the nineties being an example. Another sees noise as a form of “pure expression,” for example the abstract spatters of paint in Jackson Pollock’s work, which could be the visual analog of noise. Yet another interpretation sees noise as the “absence of meaning,” though this becomes a bit of a paradox, since meaninglessness is, in fact, a form of meaning itself.

Most noise theory eventually references Theodor Adorno, a German philosopher who argued that all elements of culture essentially end up as commodities, including art. A connoisseur of classical music, he believed that popular culture essentially collapsed music, and all art, into subtle variations upon a theme, designed to entertain an easily placated public to serve the ends of industry. In Adorno’s eyes, the avant-garde suffers the same fate, its lofty ideas similarly reduced to a product to be sold. In an article titled “Why Hardcore Goes Soft,” writer Nicholas J. Smith reflects on Adorno as he laments the experience of buying a noise album, which he equates to “paying twenty dollars for an hour of noise.” He points out how rapidly noise and experimental music get typecast as oddball:

“…[T]he standard track for modernists’ works is to be perceived as strange and dissonant, then to be appreciated as somehow artistically meaningful, and then to slip into cliché. When these stages are conflated and the strange and dissonant is immediately taken for the cliché, then art never hints at anything beyond onedimensional instrumental culture.”

The Merzbox is both enactment and satire of that concept. It’s a consumer product that nods at its own collectability while simultaneously straining the limits of what can be considered consumable by the sheer fact that it comprises fifty CDs’ worth of feedback noise. It is just about as close as you can get to an unlistenable work of music, but it looks great on a shelf.

The book will see publication soon (remember to check the website of Feral House) and we will do an interview with Michael on May 18th, so that you can send in questions which we will ask him, until May 16th to this address: [email protected] with the subject “Question for Michael Tau”. This way you can become a part of VoS and learn a lot about “Extreme Music”.