To haunt, to confront, to seduce, to strike. In night, in day, in that indecipherable moment when the sun meets the water and horizon and melts both together like glass and steel. Textures mix like wet plaster and arrive like concrete. This is the new school painfully birthed from the old school.

Sametou Sawtan (I Heard a Voice), SANAM’s second full length record, is a capsule of a burning synthesis of a racket that would make any Noise Rock or Metal musician shudder with envy and flinch with inadequacy. The many proverbial rooms this album was made in influenced the axiomatic voice of each song; like acoustics bouncing around jagged and smooth architecture — Sametou Sawtan’s voice is elusive, whispered in riddle and screamed as a spark only visible on a nocturnal drive down its dusty streets filled with secrets and the rumble of clouds overhead.

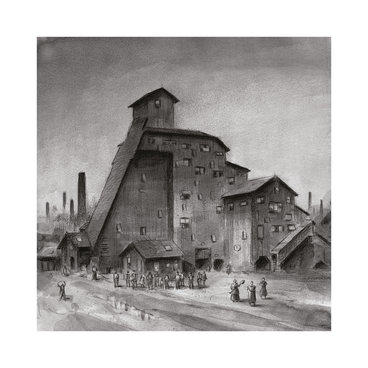

Sametou Sawtan emerges as a record built from other people’s words and yet unmistakably SANAM’s own burning core – a circle of musicians turning centuries-old poetry and scraps of borrowed language into one long, delirious present moment, like a séance held in a collapsing apartment block. In Beit Faris’ medieval stone rooms and the half-ruined flats of Byblos and Beirut, they chase that “infinite fire” where distance, exile, and the obsessive re-looping of trauma become not themes but weather systems, seeping into room tone, birdsong, the hum of faulty electrics back into themselves.

The unexpected thing is how rigorously composed this chaos is: a band once content to improvise now writing sharply contoured songs, then deliberately throwing those structures into a blender of autotune meltdowns, buzuq spirals, and pulse-quickening rhythm-section feints until “fusion” becomes something too tame a word for.

Voices arrive as ghosts — Ahmad Rami via Umm Kulthum, Omar Khayyam, Paul Chaoul, even fragments of Imam Ali — but SANAM refuse to treat them as museum pieces; instead, they are pushed through overdriven amps and cracked electronics until a mystic revelation sounds indistinguishable from feedback, from a jet overhead, from the pop of a torn microphone clipping in a DIY Parisian space.

What makes the album feel quietly transcendent in the current landscape is this refusal of spectacle: in an era of algorithmic post-genre polish, Sametou Sawtan feels like a hand-soldered transmitter picking up every stray signal of a city in perpetual aftershock and insisting that all of it – the love songs, the explosions, the jokes between takes – belongs in the same, shared, burning song.

Contrary to Post-Rock that comes from the expected places we’ve come to appreciate, SANAM’s reality is much more sobering. The stakes are higher. The fear of death, the fight for survival, and the loom of erasure, each anxious pluck imprints this grievous reality into every note.

SANAM’s music lives far less in the long arc of crescendo and catharsis and far more in the knot of the moment where beauty and terror are inseparable. Where so much Post-Rock aims at widescreen uplift or glacial melancholy, Sametou Sawtan carries an emotional weight that is granular and lived-in: the anxiety of waiting for the next siren, the tenderness of stolen ordinary hours, the stubborn absurdity of making art in conditions that do not care whether art exists at all. The guitars can howl and the drums can surge like any Mogwai-descended roar, but the emotional resonance is different: these songs don’t offer a clean purge; they leave the listener inside the loop, where attachment, fear, memory, and desire keep circling back in new, disorienting configurations.

If Post-Rock often feels like looking at the storm from a distance, SANAM sound like they’re recording from the eye of it, building a language in which transcendence is not an escape from history but a deeper, unflinching occupancy of it.